Messalina – The Most Notorious Women in Rome?

Messalina: The Most Notorious Woman in Roman History

When it comes to infamous figures in Roman history, few names can match the notoriety of Messalina. Born around 20 CE, she was not only a cousin of the infamous emperors Nero and Caligula but also ascended to the prestigious position of Empress through her marriage to Emperor Claudius.

Her life is shrouded in mystery, but her reputation as one of Rome’s most promiscuous women has endured throughout history. However, it’s essential to ask whether Messalina truly deserved this notorious reputation or if it was a result of politically motivated hostility.

A Tumultuous Marriage

Suetonius – A Woman of Abandoned Incontinence

In 37 CE, Messalina married Claudius, a man who was over 30 years her senior. At the time, Caligula still ruled as Emperor, and the union was not without controversy. Suetonius, the Roman historian, painted a vivid and scandalous portrait of Messalina’s behaviour during this period:

“Claudius took in marriage Valeria Messalina, the daughter of Barbatus Messala, his cousin. But finding that, besides her other shameful debaucheries, she had even gone so far as to marry in his own absence Caius Silius, the settlement of her dower being formally signed, in the presence of the augurs, he put her to death.”

Suetonius goes on to describe Messalina as a woman of “abandoned incontinence,” accusing her of engaging in promiscuous behaviour not only within the palace but also in the seedy streets of Rome itself.

Suetonius wrote:

“Claudius took in marriage Valeria Messalina, the daughter of Barbatus Messala, his cousin. But finding that, besides her other shameful debaucheries, she had even gone so far as to marry in his own absence Caius Silius, the settlement of her dower being formally signed, in the presence of the augurs, he put her to death.”

“She was married to Claudius, and had by him a son and a daughter. To cruelty in the prosecution of her purposes, she added the most abandoned incontinence. Not confining her licentiousness within the limits of the palace, where she committed the most shameful excesses, she prostituted her person in the common stews, and even in the public streets of the capital.”

The characteristics most predominant in him (Claudius) were fear and distrust. In the beginning of his reign, though he much affected a modest and humble appearance, as has been already observed, yet he durst not venture himself at an entertainment without being attended by a guard of spearmen, and made soldiers wait upon him at table instead of servants. He never visited a sick person, until the chamber had been first searched, and the bed and bedding thoroughly examined. At other times, all persons who came to pay their court to him were strictly searched by officers appointed for that purpose; nor was it until after a long time, and with much difficulty, that he was prevailed upon to excuse women, boys, and girls from such rude handling, or suffer their attendants or writing-masters to retain their cases for pens and styles.”

The Plot with Gaius Silius

One of the most scandalous episodes in Messalina’s life revolved around her affair with Gaius Silius, a Roman senator nominated as consul designate for 49 CE. Infatuated with Messalina, Silius divorced his wife to marry her. Shockingly, they didn’t wait for Claudius’s demise and instead committed bigamy while he was away at Ostia. Their ambitions were clear: they sought to usurp Claudius.

To further their sinister plot, Messalina and Silius even resorted to fabricating stories about Claudius’s impending murder in their dreams, terrifying the ageing emperor. However, despite Claudius’s initial reluctance, he eventually uncovered the conspiracy and summoned Messalina to answer for her actions.

Idleness, John William Godward, 1900, Public Domain.

To effect their plan to usurp Claudius the conspirators tell stories about seeing Claudius being murdered in their dreams to frighten the old man. Claudius was indeed afraid. He had Appius, one of the conspirators put to death for his stories then related the whole affair to the senate, and acknowledged his great obligation to his freedmen for watching over him even in his sleep.

Nevertheless, the plot continued. When Claudius found out about it “Messalina was ordered into the Emperor’s presence, to answer for her conduct.”

“Terror now operating upon her mind in conjunction with remorse, she could not summon the resolution to support such an interview, but retired into the gardens of Lucullus, there to indulge at last the compunction which she felt for her crimes, and to meditate the entreaties by which she should endeavour to soothe the resentment of her husband.

“In the extremity of her distress, she attempted to lay violent hands upon herself, but her courage was not equal to the emergency. Her mother, Lepida, who had not spoken with her for some years before, was present upon the occasion, and urged her to the act which alone could put a period to her infamy and wretchedness. Again she made an effort, but again her resolution abandoned her; when a tribune burst into the gardens, and plunging his sword into her body, she instantly expired.”

Suetonius says that when Claudius heard about her death he simply asked for another chalice of wine. Indicating he was either forgetful, as he was about many things or callus.

The Roman Senate then ordered a damnatio memoriae *so that Messalina’s name was removed from all public and private places and all statues of her were taken down. *See: Damnatio memoriae—Roman sanctions against memory, for more information

Suetonius paints Messalina as a whore and a woman who sleeps with lower class men – either way, she likes her sex rough and dirty which is not the hallmark of a respectable Roman matron let alone an Empress. What passes for history when it comes to Messalina is political and social annihilation. Accusations of sexual excess were and still are a tried and tested smear tactic against women. In this case, they were the result of politically motivated hostility.

Pliny The Elder- Messalina The Prostitute

Athenais, John William Godward, 1908, Public Domain.

The account of Messalina competing with the prostitute Scylla to see who could have sex with the most people in one night was first recorded by Pliny the Elder. Pliny says that, with 25 partners, Messalina won.

Pliny was discussing the differences between the sexual habits of human beings and animals when he wrote the following about Messalina and the nymphomaniac contest.

“Messalina, the wife of Claudius Cæsar, thinking this a palm quite worthy of an empress, selected, for the purpose of deciding the question, one of the most notorious of the women who followed the profession of a hired prostitute; and the empress outdid her, after continuous intercourse, night and day, at the twenty-fifth embrace.”

Juvenal – The She-Wolf

The Roman poet Juvenal tells in his sixth satire that the Empress used to work clandestinely all night in a brothel under the name of the She-Wolf (Lycisca). Juvenal coined the phrase frequently applied to Messalina thereafter, meretrix augusta (the imperial whore). In so doing, he coupled her reputation with that of Cleopatra, another victim of imperially directed character assassination, whom the poet Propertius had earlier described as meretrix regina (the harlot queen).

John William Godward, The Mirror, 1899. Pubic Domain.

“Hear what Claudius had to endure. As soon as his wife perceived he was asleep, this imperial harlot, that dared prefer a coarse mattress to the royal bed, took her hood she wore by nights, quitted the palace with but a single attendant, but with a yellow tire concealing her black hair; * entered the brothel warm with the old patchwork quilt, and the cell vacant and appropriated to herself. Then took her stand with naked breasts and gilded nipples, assuming the name of Lycisca, and displayed the person of the mother of the princely Britannicus, received all comers with caresses and asked her compliment, and submitted to often-repeated embraces.”

*To conceal her identity, she wore a blonde wig over her black hair.

Describing the bigamist marriage he wrote:

“She is long since seated with her bridal veil all ready: the nuptial bed with Tyrian hangings is openly prepared in the gardens, and, according to the antique rites, a dowry of a million sesterces will be given; the soothsayer and the witnesses to the settlement will be there! Do you suppose these acts are kept secret; intrusted only to a few? She will not be married otherwise than with all legal forms. Tell me which alternative you choose.”

“Shall he accept, or not, the proffered bride,

And marry Cæsar’s wife? hard point, in truth:

Lo! this most noble, this most beauteous youth,

Is hurried off, a helpless sacrifice

To the lewd glance of Messalina’s eyes!

–Haste, bring the victim: in the nuptial vest

Already see the impatient Empress dress’d;

The genial couch prepared, the accustomed sum

Told out, the augurs and the notaries come.

“But why all these?” You think, perhaps, the rite

Were better, known to few, and kept from sight;

Not so the lady; she abhors a flaw,

And wisely calls for every form of law.

But what shall Silius do? refuse to wed?

A moment sees him numbered with the dead.

Consent, and gratify the eager dame?

He gains a respite, till the tale of shame,

Through town and country, reach the Emperor’s ear,

Still sure the last–his own disgrace to hear.

Then let him, if a day’s precarious life

Be worth his study, make the fair his wife;

For wed or not, poor youth, ’tis still the same,

And still the axe must mangle that fine frame!

Tacitus

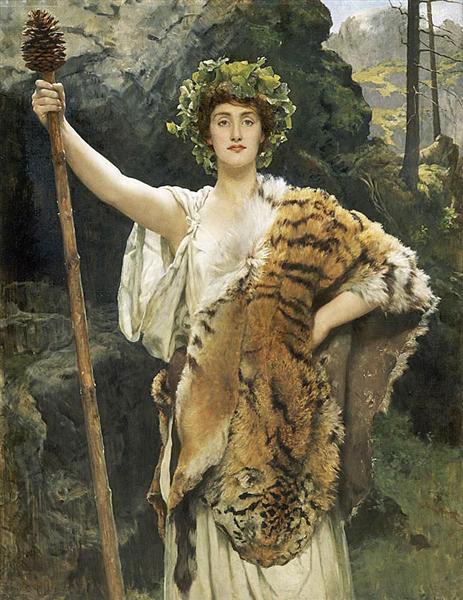

The Priestess of Bacchus, John Collier, 1889. Public Domain

Messalina’s most famous affair is the one she had with senator Gaius Silius. It is said she told Silius to divorce his wife, which he did and that they planned to kill Claudius and make Silius Emperor.

Their adulterous wedding was a Bacchanalian affair.

According to Tacitus “Messalina had never given voluptuousness a freer rein. Autumn was at the full, and she was celebrating a mimic vintage through the grounds of the house. Presses were being trodden, vats flowed; while, beside them, skin-girt (naked) women were bounding like Bacchanals excited by sacrifice or delirium. She herself was there with dishevelled tresses and waving thyrsus; at her side, Silius with an ivy crown, wearing the buskins and tossing his head.”

Was Her Reputation Deserved?

The problem for Messalina is that the Roman historians who relayed these stories about her, principally Tacitus and Suetonius, wrote them some 70 years after the events in a hugely hostile political environment where everything related to the imperial line to which Messalina had belonged was being trashed. Suetonius’ history is a great read but it is largely anti-Julio-Claudian scandal-mongering – they all get a bad press from him.

Tacitus claims to be transmitting ‘what was heard and written by my elders’ without naming sources other than the memoirs of Agrippina the Younger, who had arranged to displace Messalina’s children in the imperial succession and was therefore particularly interested in blackening her predecessor’s name.

Valeria Messalina came from the most distinguished Roman social circles, she was no two-bit harlot. She is portrayed as a scheming, manipulative and greedy liar who has no compunction in bringing down innocent people who she dislikes or who get in her way which it seems has an element of truth about it.

The female members of Claudus’s family were a special target for Messalina’s spite. Within the first year of Claudius’ reign, his niece Julia Livilla, only recently recalled from banishment upon the death of her brother Caligula, was exiled again on charges of adultery with Seneca the Younger – accusations made by Messalina. Claudius ordered Julia Livilla’s execution soon after which of course did not make Messalina any friends.

Messalina also considered Agrippina’s son Lucius (Nero) a threat to her son Britannicus. She sent assassins to strangle Lucius during his siesta. But the assassins bungled the job. They saw what they thought was a snake on his pillow and left, perhaps thinking the snake would kill him and spare them the guilt. The snake turned out to be a snakeskin and after that Agrippina considered it a lucky charm. She gave it to her son Nero when he became Emperor to protect him. In 47, Agrapina’s second husband Crispus died, leaving her a wealthy widow. Later that year at the Secular Games, Agrippina and Nero were cheered more loudly than Messalina and Britannicus raising Messalina’s ire and Agrippina soon found herself implicated in allegations of illegal “magical and superstitious practices”. According to Tacitus, Messalina was only prevented from further persecuting Agrippina because she was distracted by her new lover, Gaius Silius.

Messalina was clearly a schemer but so was everyone else. She was only doing what most other women in her position were doing – she was protecting her own son and her own position. However, when Messalina took up with Silius it seems she was intent on breaking the circle of ‘freedmen’ surrounding Claudiu, perhaps most particularly Narcissus. These men were totally loyal and dependent on Claudius and had a great influence on him. Why she was so hostile to them remains a mystery. Narcissus, the man who revealed Messalina’s bigamist marriage to Claudius was one of Claudius’s freedmen and was probably glad she’d gone too far and he could now see the back of her.

The pair had once been allied against Senator Gaius Appius Junius Silanus. Silanus, the former governor of the province of Hispania Tarraconensis married Messalina’s mother Domitia Lepida in CE 41. He now played an important role at court, but evidently soon incurred the hatred of Messalina and Narcissus. They, therefore, worked towards his fall. Cassius Dio admittedly gives the only motive for Messalina’s enmity that her stepfather refused her offer of love. According to SuetoniusNarcissus told Claudius he had dreamed that Silanus wanted to murder him. Messalina said she had had the same dream and Claudius being convinced of the truth of dreams had Silanus executed.

In 46 CE she poisoned Marcus Vinicius, the husband of Julia Livilla, whom she had eliminated four years earlier because he allegedly had not wanted to enter into an affair with her. In late 46 or early 47, she removed the young Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, the husband of Antonia, Claudius’s daughter by a previous marriage. One version of his demise has him executed for a homosexual relationship. Again it seems she was removing possible rivals to Britannicus.

The earliest and the only not entirely negative source about Messalina is the drama Octavia, attributed to Seneca, about the life of her daughter Octavia. Only Nero uses the expression Incesta genetrix – unchaste mother-in-law, in the second act, as an argument to accuse Octavia of adultery, while Messalina appears more passive in the marriage with Silius.

The account in Tacitus ‘ Annals of Claudius’ first years in reign is lost; the surviving second part of this work begins with the description of Valerius Asiaticus’ case in Book 11. Hence, more details are known about Messalina’s last year of life. [41] Tacitus’ picture is, however, marked by clear aversion, which is based on his criticism that Claudius did not seek advice from the senators, but from people who were unsuitable for them, such as women and freedmen. De vita Caesarum, which was written around the same time, in SuetonsMessalina is almost only mentioned in connection with her wedding to Silius, to which Iuvenal also refers in his 10th satire. A parallel report on Tacitus is provided by Cassius Dio, which has only been handed down in excerpts (Book 60).

Messalina’s Legacy to the World of Art

Nathaniel Richards’ The Tragedy of Messalina, Empress of Rome

The Tragedy of Messalina, Empress of Rome ( was entered in the Stationer’s Register on October 2 1639, and was published in 1640. The cast list attached to the 1640 quarto edition has been cited as evidence that it was staged prior to this date, and by the King’s Revels. William Cartwright Senior played Claudius, John Barrett, and Messalina. The play was staged between 18 July 1634 and 12 May 1636.

Richards’ Messalina is a wildly exaggerated caricature of the historical woman. Richards stretches the evidence of his sources to depict a character beyond recognition in Roman histories. His Messalina is depraved, wicked and utterly irredeemable. Richards insists on Messalina’s beauty, although none of the authorities speak of it specifically; both Silius and Claudius are unable to resist her bewitching eyes, which are demon-like in their power. She employs methods of torture to force men into her bed. Even when she has been condemned to death, she shows no remorse for her appalling crimes. The episode with Scylla, the prostitute whom Messalina was said to have challenged to a contest, is referred to repeatedly in the play.

The destructiveness of succumbing to sexual temptation is the clear theme of the play, and references to lust are habitually linked with motifs of poison and disease. The inherent virtue of Silius is emphasised in his speech moralising on the power of lust, which begets murder and makes a man a devil. Messalina is depicted as a poisonous influence, ‘with a pleurisy of lust‘ (II.ii.39) literally running through her veins, and male characters are repeatedly corrupted by her influence. Female sexuality is linked to violence and Messalina is linked to images of hell. Her power to seduce is repeatedly linked to the supernatural; she summons the Furies to invoke her lust, emphasising her utterly sub-human and barbaric nature.

‘Of Roman Messalina; the play is new,

And by Rome’s famed historians confirmed true.

We hope you’ll not distaste it, nor us blame,

Where spots of life are acted to sin’s shame.

Tell me, I pray, can there be no content?

To see high towering sin’s just punishment

And virtue’s praise, insatiate lust to die,’ (Extra from the Prologue, 1634.)

Richard’s Messalina, a thinly veiled attack on Queen Henrietta Maria, the wife of Charles I and what was commonly perceived to be her corrupting influence at Court. In the period of Stuart rule, monarchs were referred to as Emperors, and the contemporary audience could not have failed to notice the resemblance between Richard’s Claudius, with his limp and stutter, whom his mother, Antonia, frequently called an abortion of a man, that had been only begun but not finished, by nature, and their King, who spoke with a stammer and walked with a limp after suffering from rickets in his leg. Neither Charles nor Claudius were expected to live beyond infancy, and both became rulers by mere accident: Claudius was proclaimed Emperor following Caligula’s death, and Charles became the sole heir when his brother Henry, Prince of Wales, died unexpectedly. It would have been impossible for Richard’s audience to ignore his analogies between the ‘God of the Britons’ whose son, Britannicus, was named after the conquest, and the current King of England.

Messalina: A Magnificent Novel of the Most Wicked Woman in History 1959

Jack Oleck’s novel Messalina: A Magnificent Novel of the Most Wicked Woman in History (1959/60) depicts a woman who is ‘beautiful…tantalising…deadly…one of the most depraved, unscrupulous women in all history’. The novel depicts – often in graphic detail – Messalina’s liaisons with Isaax, her slave, Decimus, Caligula and Vitellius.

Robert Graves

Graves began writing his famous set of 5 Roman novels in1929 on the island of Majorca where he lived with the American poet Laura Riding. The first editions were published in 1934. They were acquired by Penguin in 1943 and have enjoyed continuous success ever since. In the novels, Claudius hides behind his reputation as a cripple and an idiot to live to a ripe old age. Graves makes him the central figure in the books and their narrator but this Claudis is an unreliable historian. The most well-known re-telling of the story is Robert Graves’s follow-up to his novel I Claudius, Claudius the God and His Wife Messalina, and its hugely popular television dramatisation, starring Derek Jacobi. Both are largely based on Suetonius and portray Claudius with sympathy, duped by a scheming and manipulative wife.

Messalina On The Silver Screen

Her notorious story has had several outings on the silver screen – 1951, 1960, 1981

1951

1960

1960

Scheming Messalina marries Roman Emperor Claudius but goes too far with a gladiator.Director: Vittorio Cottafavi

Writers: Ennio De Concini (screenplay), Ennio De Concini (story)

Stars: Belinda Lee, Spyros Fokas, and Carlo Giustini

1981

The seductive Messalina (Betty Roland) will stop at nothing to become the most powerful woman in Rome. Gaining the attention of Emperor Caligula (Gino Turini). rectors: Bruno Mattei (as Vincent Dawn), Antonio Passalia (as Anthony Pass) |

Writer: Antonio Passalia (as Anthony Pass)

Stars: Vladimir Brajovic, Betty Roland, Françoise Blanchard

Sources:

The Annals of Tacitus published in Vol. IV of the Loeb Classical Library edition of Tacitus, 1937.

THE LIVES OF THE TWELVE CAESARS, C. Suetonius Tranquillus; HIS LIVES OF THE GRAMMARIANS, RHETORICIANS, AND POETS. Trans: Alexander Thomson, M.D. revised and corrected by T.Forester, Esq., A.M. Project Gutenburg.

Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, CHAP. 83. (63.)—GENERATION OF ALL KINDS OF TERRESTRIAL ANIMALS.John Bostock, M.D., F.R.S., H.T. Riley, Esq., B.A., Ed.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Satires of Juvenal, Persius, Sulpicia, and Lucilius, by Decimus Junius Juvenal and Aulus Persius Flaccus and Sulpicia and Rev. Lewis Evans and William Gifford.

Gilmore, John T. (2017). Satire. Routledge. – via Google Books.

Barbara Levick (1990). Claudius. Yale University Press.

Anthony Barrett (1996). Agrippina: Sex, Power and Politics in the Early Roman Empire. Yale University Press.

Alexander Demandt : The private life of the Roman emperors. 2nd Edition. Beck, Munich 1997.

Werner Eck : The Julian-Claudian family. In: Hildegard Temporini-Countess Vitzthum (Hrsg.): Die Kaiserinnen Roms. From Livia to Theodora. Beck, Munich 2002.

Gertrud Herzog-Hauser , Friedrich Wotke : Valerius 403). In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classical antiquity science (RE). Volume VIII A, 1, Stuttgart 1955, Col. 246-258.

Franesco Mazzei: Messalina. Heyne, Munich 1985.

ImDB Film Catlogue.

https://extra.shu.ac.uk/emls/iemls/renplays/mess%20intro.htm#

About Julia Herdman

Julia Herdman writes historical fiction that puts women to the fore. Her latest book Sinclair, Tales of Tooley Street Vol. 1. is Available on Amazon – Paperback £10.99 Kindle £0.99 Also available on:

Recent Comments